The next file inside src/ is bash.h.

Code

I happen to know from my limited previous experience with C that a .h file is a header file. I look up the GCC docs on header files, and read the first few paragraphs:

So header files contain C definitions which will be used in multiple files. They’re useful if you want to avoid duplicating the logic contained in the header file everywhere it’s needed. If that logic needs to change, you can make the change in only one place- the header file.

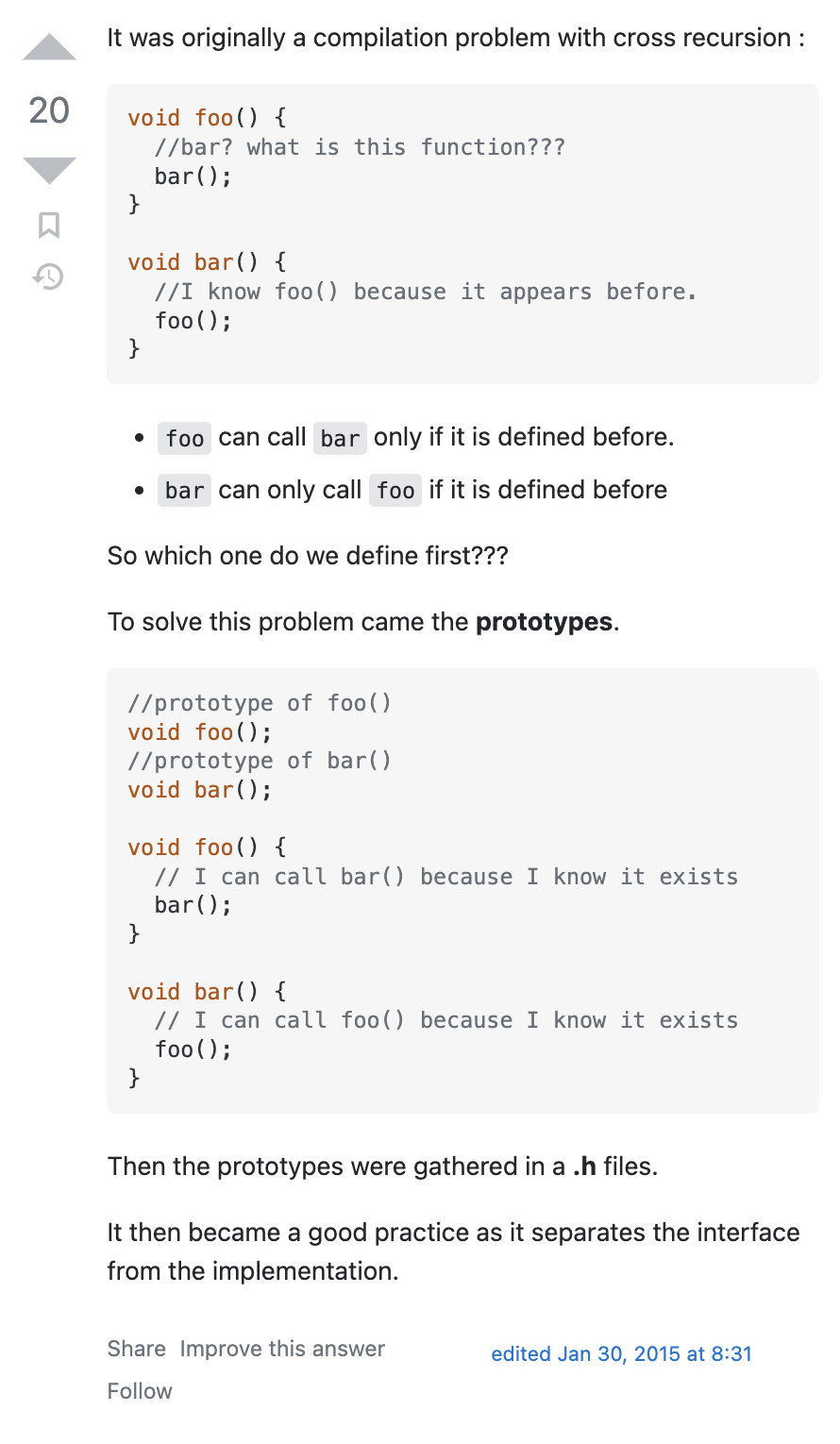

To get confirmation, I Google “why does C use header files” and I find this StackOverflow post, which is much clearer. The first answer I read talks about the benefits of avoiding problems with functions which call each other:

It also mentions the benefits of separating interface (i.e. the function’s signature, or the combination of the function name / parameters it takes / return value) from implementation (i.e. what it does under-the-hood).

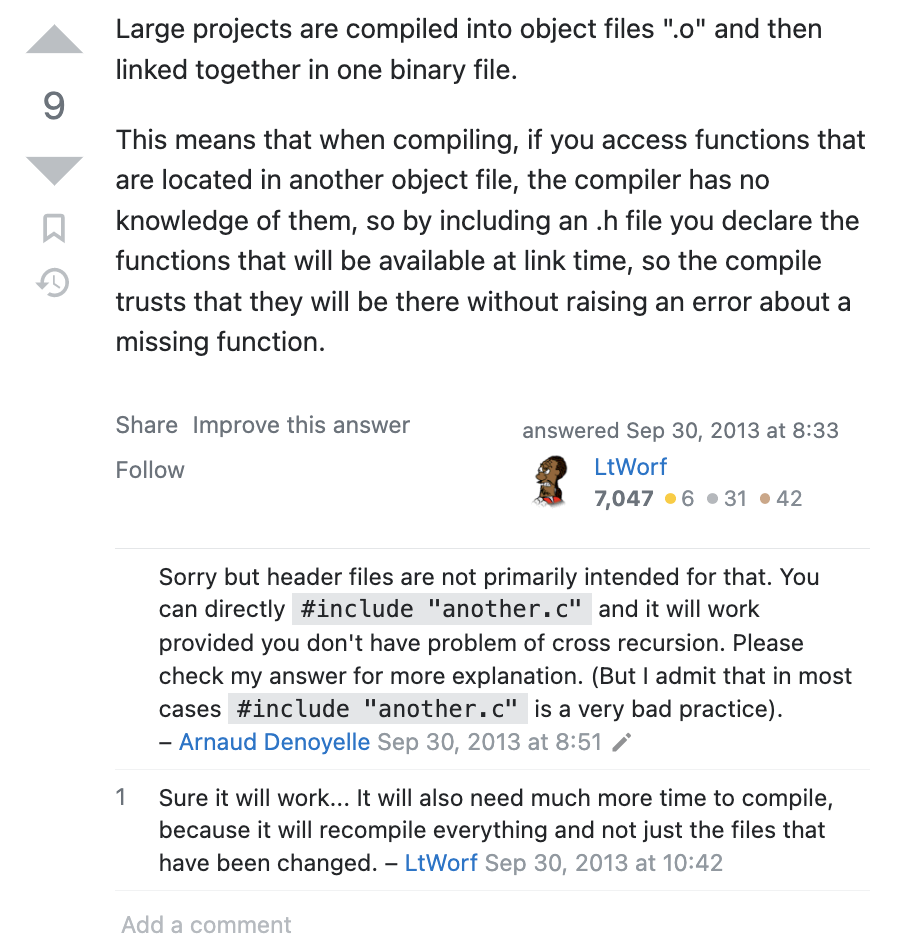

Another benefit is mentioned in the following answer:

Similar to the previous answer, this 2nd answer also touches on missing function definitions. However in the comments it also touches on performance issues. If we use header files, we gather (i.e. compile) all the data definitions and function interfaces together at “compile time”, and there’s no need to re-compile them later (at “link time”). The fact that we don’t have to re-compile means our code can run faster.

So there are multiple reasons why we might use header files. In our case, we only have one file that includes bash.h- a file named realpath.c (which we’ll look at later). Because the logic inside bash.h doesn’t appear to be used in other files, it’s possible that we don’t strictly need to use the header file strategy here. Could we have included these declarations directly in realpath.c? I decide to test this with an experiment.

Experiment- including header logic directly in a C file

In realpath.c, I comment out the include statement which imports bash.h, and paste the contents of bash.h directly at the top of realpath.c, directly after the next two include statements:

// #include "bash.h"

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#ifndef __BASH_H__

#define __BASH_H__

#define EXECUTION_SUCCESS 0

#define EXECUTION_FAILURE 1

#define EX_USAGE 258

#define BUILTIN_ENABLED 1

...

When I run make clean followed by make inside the src/ directory, it works fine- the libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib file is successfully built. This leads me to believe that the authors used the header file strategy more out of convention than necessity (though I could be wrong).

Ensuring a header file is only included once

On to the first block of code:

#ifndef __BASH_H__

#define __BASH_H__

...

#endif

Again from my very brief prior experience with C, I know that the above code means “if the constant BASH_H isn’t defined, then define it”. Everything in between ifndef and endif (i.e. the bulk of the contents of this header file) is only executed if __BASH_H__ has not yet been defined. Here is some documentation on ifndef and how/why it’s used:

The last sentence appears to be what’s happening here- we’re avoiding the problem of double-inclusion by wrapping the main body of the header file inside an ifndef + endif block. I subsequently confirmed this via a question I asked here, in StackExchange.

Defining constants for our realpath builtin

Next block of code:

#define EXECUTION_SUCCESS 0

#define EXECUTION_FAILURE 1

#define EX_USAGE 258

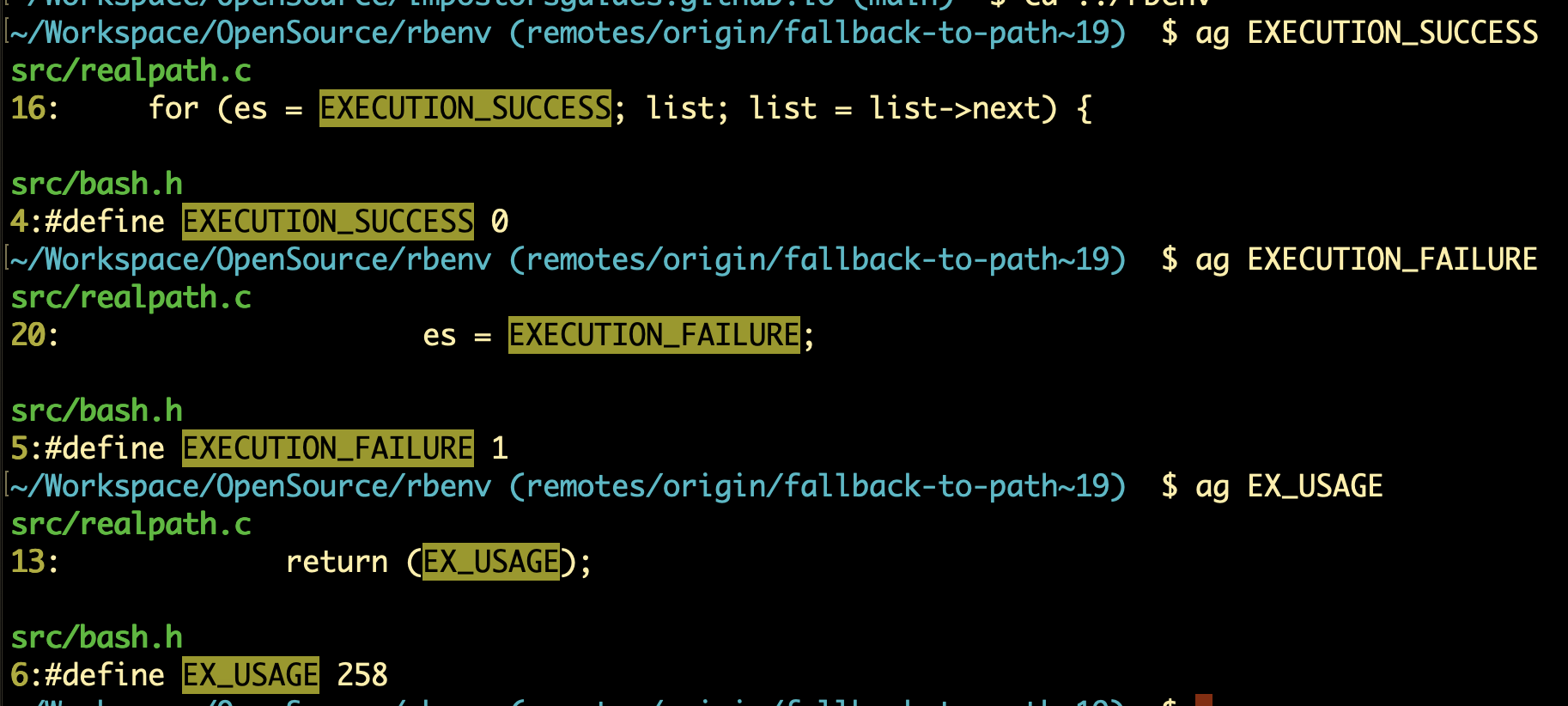

These are more macro definitions. I was curious where the variables defined by these macros are used, so I searched the codebase for them. Looks like they’re all used in realpath.c:

We’ll wait until we get to realpath.c before analyzing exactly what these do. But judging by their names (EXECUTION_SUCCESS, EXECUTION_FAILURE, etc.), they appear to be related to the exit status of the more-performant realpath implementation.

Ensuring our new realpath builtin is enabled

Next block of code:

#define BUILTIN_ENABLED 1

Another macro definition. This one is also exclusively used by realpath.c, so let’s punt on exploring this one as well. There’s a chance we may do the same thing for the remaining macros in this file, as well.

Defining data types for use in the realpath builtin

The rest of the code in this header file is a series of definitions for data types which our builtin will use.

word_desc-

Here’s the first one:

typedef struct word_desc {

char *word;

int flags;

} WORD_DESC;

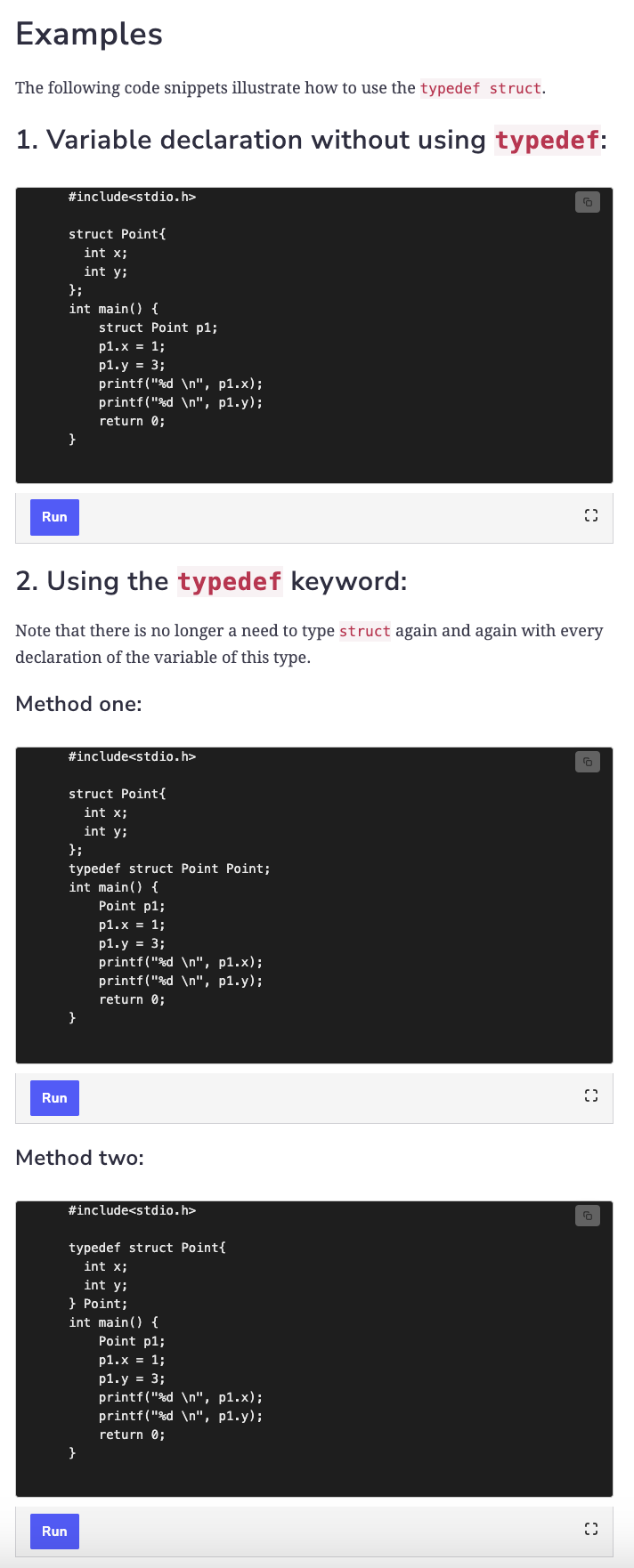

I’ve seen this syntax before, in a previous attempt to learn C, but I need a refresher. I Google “what is typedef struct c”, and find this page (I started by searching directly on gcc.gnu.org/, but couldn’t quickly find anything relevant). Here’s a before-and-after example of how typedef struct is used in C:

The section marked “Method two” above most closely resembles what the code in bash.h does. In our case, that means that instead of typing:

struct word_desc {

char *word;

int flags;

};

...

struct word_desc foo;

foo.word = "abc";

foo.flags = 5;

We can instead type:

typedef struct word_desc {

char *word;

int flags;

} WORD_DESC;

WORD_DESC foo;

foo.word = "abc";

foo.flags = 5;

In other words, typedef struct makes it easier to treat our C structs as regular object variables, the way we might with an object in Javascript.

The next block of code is another typedef struct invocation:

typedef struct word_list {

struct word_list *next;

WORD_DESC *word;

} WORD_LIST;

Since there’s nothing new in this example, we’ll move on to the next block of code:

typedef int sh_builtin_func_t(WORD_LIST *);

(stopping here; 3870 words)

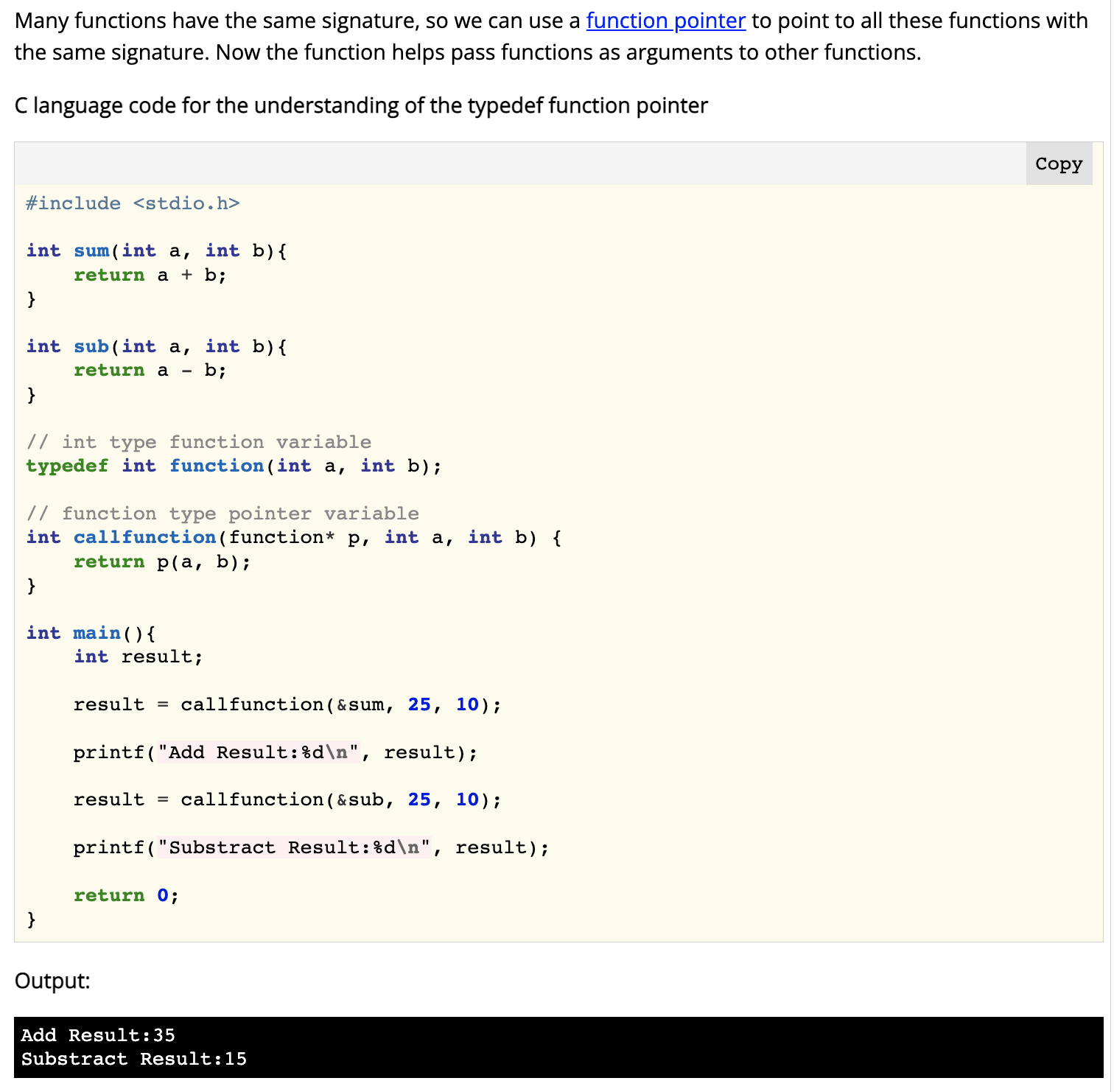

This code was confusing to me at first. I see the use of typedef again, but it looks different from when it was used with a struct. Here we’re using it with the keywords int and what looks like a function call (sh_builtin_func_t(WORD_LIST *)). I Google “typedef function” and, after reading through a few dead-end pages, I found this page, which includes the following example code and description:

We can see typedef int function(int a, int b); in the middle of the screenshot, and then int callfunction(function* p, int a, int b) after that. So a function named callfunction is defined, which takes as parameters a function and two int values. And since any function which takes in two int params can be passed to callFunction, we need to define an abstract interface first, which we do using the typedef line.

In the case of our code, it looks like we define a similar abstract interface on this line of code. In our case, we’re defining the abstract interface named sh_builtin_func_t, which is subsequently used in the builtin struct at the end of the file. Any function which takes in a WORD_LIST type and returns an int type would be an acceptable concrete implementation of this abstract sh_builtin_func_t function interface.

Last block of code:

struct builtin {

char *name;

sh_builtin_func_t *function;

int flags;

char * const *long_doc;

const char *short_doc;

char *unused;

};

Here we’re wrapping up this file by defining the aforementioned builtin struct. This data type has a few properties:

A name property (of type char, aka a string)

A function property (of the aforementioned sh_builtin_func_t abstract interface type)

A flags property (of type int)

A long_doc property (of type char, aka a string; also, this is constant, so it can’t be changed)

A short_doc property (of type char, aka a string; also, this is constant, so it can’t be changed)

An unused property (of type char, aka a string)

After a grep for this builtin struct, I find that it’s used here, in realpath.c. We’ll examine how it’s used when we get to that file.

OK, so I get how the .h and .c files fit in with each other and what they seem to be doing, but where does their end result actually get used?

I look up the Github history of these files, and find this commit, which includes the original addition of the Makefile. It references the CC variable that we saw defined earlier, which makes me think that running make will somehow run gcc, which will somehow be smart enough to bundle all the .c and .h files together and somehow produce the rbenv-realpath.dylib file which this line of code then maps into a new definition of the realpath command, via the enable builtin? There’s a lot of unknown unknowns here, but I feel like I’m at least directionally correct in the above. If I want to firm up my understanding a bit more, I think the next step is to research how a Makefile works.

(stopping here; 4380 words)

Learning Makefiles was a bit of an arduous process. It involved a lot of reading and tutorial completion; it wasn’t nearly as simple as looking up a simple answer on StackOverflow. First I read this tutorial, which was a good and (thankfully) brief step-by-step introduction. My take-aways from this page were:

- “Makefiles are a simple way to organize code compilation.”

- “(The non-Makefile) approach to compilation has two downfalls. First, if you lose the compile command or switch computers you have to retype it from scratch, which is inefficient at best. Second, if you are only making changes to one .c file, recompiling all of them every time is also time-consuming and inefficient.”

- “

makewith no arguments executes the first rule in the file.” - “…by putting the list of files on which the command depends on the first line after the :,

makeknows that the rule needs to be executed if any of those files change.”

Next I check out this tutorial, which is more comprehensive. My take-aways from this one were:

- “Makefiles are used to help decide which parts of a large program need to be recompiled.”

- “In the vast majority of cases, C or C++ files are compiled.”

- “Other languages typically have their own tools that serve a similar purpose as Make.”

- “For Java, there’s Ant, Maven, and Gradle. Other languages like Go and Rust have their own build tools.”

- “Interpreted languages like Python, Ruby, and Javascript don’t require an analogue to Makefiles. The goal of Makefiles is to compile whatever files need to be compiled, based on what files have changed. But when files in interpreted languages change, nothing needs to get recompiled. When the program runs, the most recent version of the file is used.”

- “There are a variety of implementations of Make (i.e. not just GNU Make)…”

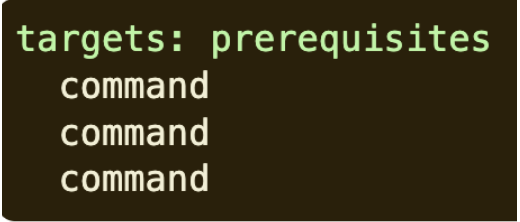

- A Makefile consists of a set of rules. A rule generally looks like this:

- The targets are file names, separated by spaces. Typically, there is only one per rule.

- The commands are a series of steps typically used to make the target(s). These need to start with a tab character, not spaces.

- The prerequisites are also file names, separated by spaces. These files need to exist before the commands for the target are run. These are also called dependencies.

- If no dependencies / prerequisites are specified, then running

makemore than once will not result in that rule being re-run, even if the rule’s associated file should be re-compiled.

The previous link also contains an embedded Youtube video, from which I learned the following:

- The dependencies referenced to the right of a “:” symbol correspond to rule names further down (i.e. names to the left of subsequent “:” symbols).

makechecks whether files need to be re-compiled by checking theupdated_attimestamps of the generated files as well as the dependencies of those files. If dependency timestamps are all older the target timestamps, no re-compilation will happen whenmakeis re-run.- However, if a dependency has an

updated_attimestamp which is newer than the file which depends on it, then a re-compilation is necessary. - If a rule’s commands don’t generate any file, those commands will be re-run every time

makeis re-run.

(stopping here; 4889 words)

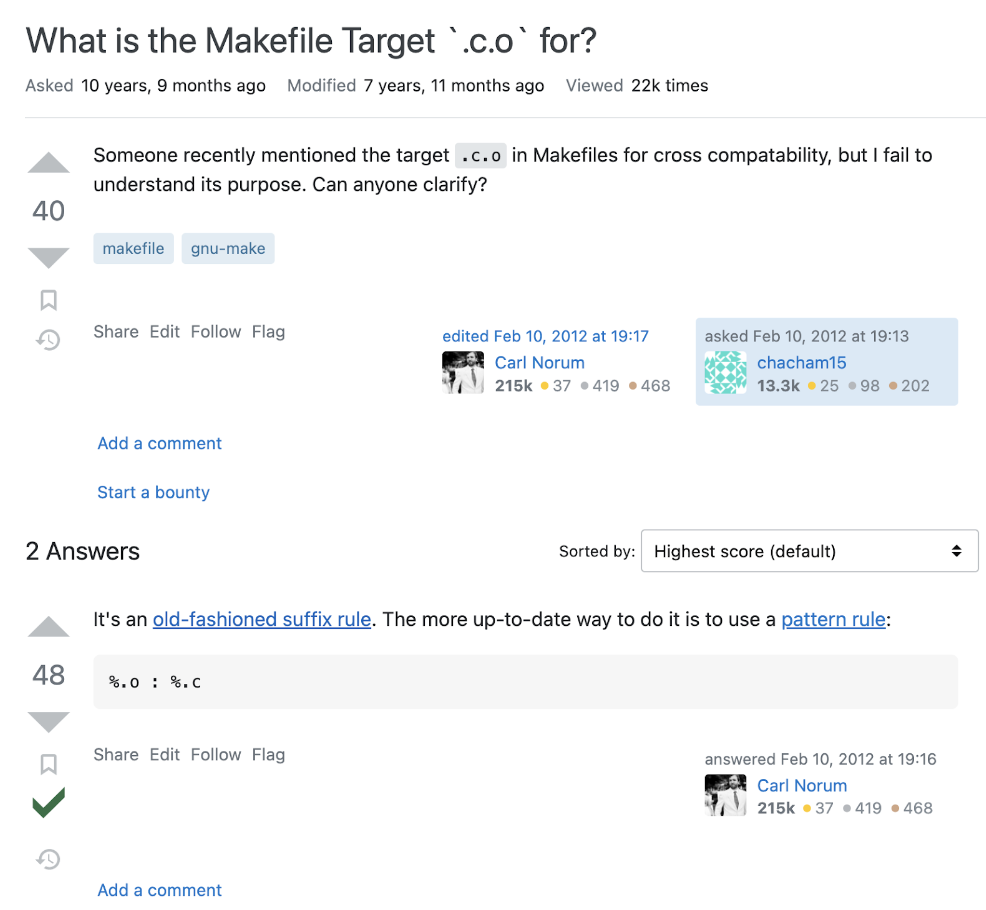

After reading the above, I’ve learned a lot. One last thing I want to learn is what “.c.o:” means here:

My first thought was that this rule creates a hidden dotfile named “c.o”. But when I ran make and did an ls -la search for any dotfiles, I didn’t find any, so I concluded that this is not correct. I then Googled ‘makefile “.c.o:”’, and found a useful result right away:

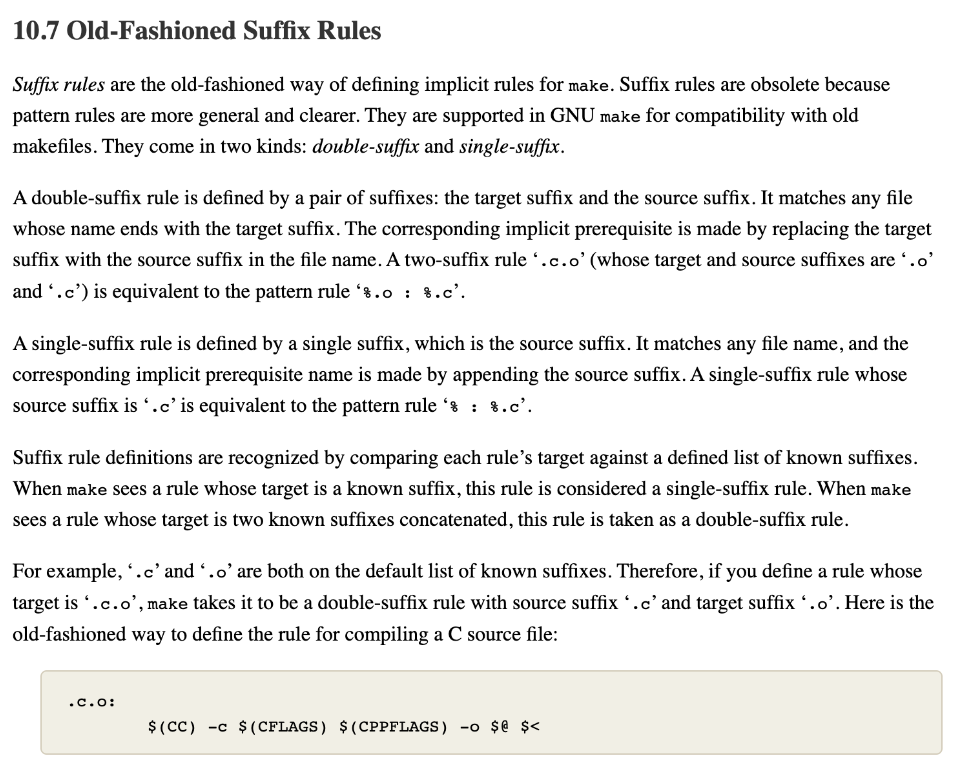

I see the link to the documentation on old-fashioned suffix rules, so I go there:

From this page, I learn that “.c.o” is actually a common (and obsolete) example of a “double-suffix rule”. In particular, this passage stands out:

A double-suffix rule is defined by a pair of suffixes: the target suffix and the source suffix. It matches any file whose name ends with the target suffix. The corresponding implicit prerequisite is made by replacing the target suffix with the source suffix in the file name. A two-suffix rule ‘.c.o’ (whose target and source suffixes are ‘.o’ and ‘.c’) is equivalent to the pattern rule ‘%.o : %.c’.

I take this to mean that the rule will look for each file with a suffix of “.c”, and use the command(s) to produce a file with the same filename as the target, but with “.o” instead of a “.c” as the file extension.

At this point, I feel like I’ve learned enough entry-level Makefile info to take a stab at understanding RBENV’s Makefile.

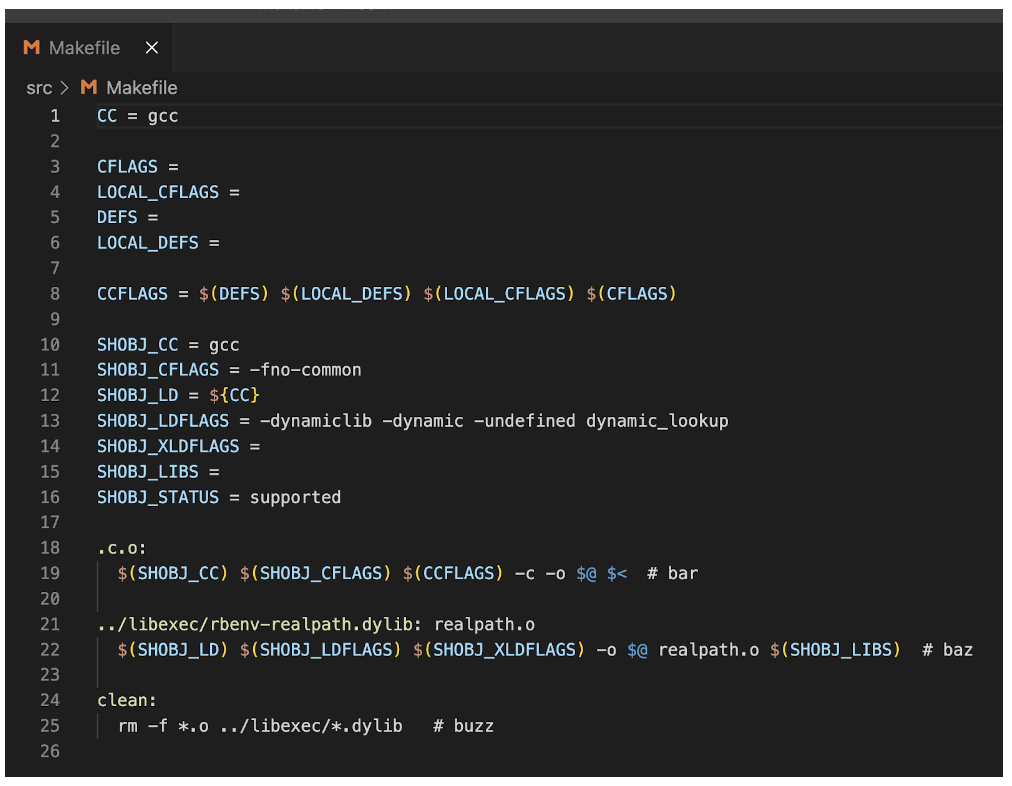

I want to make it dead-easy to see which rules run in which order, so I add the following comments (‘bar’, ‘baz’, and ‘buzz’) to the ends of these lines in “Makefile.in”:

.c.o:

$(SHOBJ_CC) $(SHOBJ_CFLAGS) $(CCFLAGS) -c -o $@ $< # bar

../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib: realpath.o

$(SHOBJ_LD) $(SHOBJ_LDFLAGS) $(SHOBJ_XLDFLAGS) -o $@ realpath.o $(SHOBJ_LIBS) # baz

clean:

rm -f *.o ../libexec/*.dylib # buzz

I then run the configure script and verify that the new “Makefile” includes the comments:

Before running make, I do an ls -la to see which files already exist:

$ ls -la

total 72

drwxr-xr-x 8 myusername staff 256 Mar 19 11:01 .

drwxr-xr-x 19 myusername staff 608 Mar 18 11:41 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 519 Dec 2 00:43 Makefile

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 610 Mar 19 10:59 Makefile.in

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 496 Mar 12 16:41 bash.h

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 954 Mar 18 11:41 configure

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 832 Mar 12 16:41 realpath.c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 14696 Mar 18 11:41 shobj-conf

I then run make in this directory:

$ make

gcc -fno-common -c -o realpath.o realpath.c # bar

gcc -dynamiclib -dynamic -undefined dynamic_lookup -o ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib realpath.o # baz

Cool, so the rule on line 18 runs first, and then the rule on line 21 runs next (also last, since there are only two non-“clean” rules here).

I then re-run ls -la to see which new files have been created:

$ ls -la

total 80

drwxr-xr-x 9 myusername staff 288 Mar 19 11:03 .

drwxr-xr-x 19 myusername staff 608 Mar 18 11:41 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 546 Mar 19 11:03 Makefile

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 610 Mar 19 10:59 Makefile.in

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 496 Mar 12 16:41 bash.h

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 954 Mar 18 11:41 configure

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 832 Mar 12 16:41 realpath.c

-rw-r--r-- 1 myusername staff 1424 Mar 19 11:03 realpath.o

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 14696 Mar 18 11:41 shobj-conf

NOTE- ignore the total 72 vs total 80 here. We did not add 8 new files. The number mentioned by total is explained in the man entry for ls:

The listing of a directory’s contents is preceded by a labeled total number of blocks used in the file system by the files which are listed as the directory’s contents

For more info on blocks, see this page from O’Reilly.

Looks like only realpath.o was created, at least in this directory. I do note that the 2nd rule specifies ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib as the target file, so I’m guessing that was created. I run ls -la ../libexec to see whether it’s there or not:

$ ls -la ../libexec

total 312

drwxr-xr-x 28 myusername staff 896 Mar 19 11:03 .

drwxr-xr-x 19 myusername staff 608 Mar 18 11:41 ..

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 2894 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 632 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv---version

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 812 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-commands

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 562 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-completions

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 1095 Mar 12 16:41 rbenv-exec

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 894 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-global

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 3534 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-help

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 1247 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-hooks

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 2541 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-init

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 1376 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-local

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 1022 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-prefix

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 49584 Mar 19 11:03 rbenv-realpath.dylib

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 4403 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-rehash

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 111 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-root

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 444 Mar 1 18:04 rbenv-sh-rehash

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 2845 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-sh-shell

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 380 Feb 28 08:35 rbenv-shims

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 498 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-version

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 658 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-version-file

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 501 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-version-file-read

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 447 Feb 28 08:35 rbenv-version-file-write

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 836 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-version-name

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 458 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-version-origin

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 2318 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-versions

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 767 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-whence

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 1714 Mar 18 11:41 rbenv-which

Yep, that’s the only file with a timestamp of today’s date (Nov 27), apart from the current and parent directories “.” and “..” at the top of the output.

Now I’m curious whether I can get this Makefile to generate “.o” files other than “realpath.o”. Successfully doing so might solidify my understanding of the double-suffix rule that I see for rule #1.

I create a file named “foo.c” in the same directory as “realpath.c”, which looks like this:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

printf("Hello world\n");

}

Pretty simple stuff. I compile this file and run the binary which is output, to make sure it works as expected:

$ gcc foo.c -o foo

$ ./foo

Hello world

Then I rm foo as well as the “realpath.o” and “../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib” files that were generated the last time I ran make. Then I re-run make and check for newly-generated files via “ls”:

$ rm foo realpath.o ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib

$ make

gcc -fno-common -c -o realpath.o realpath.c # bar

gcc -dynamiclib -dynamic -undefined dynamic_lookup -o ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib realpath.o # baz

Weird, I don’t see the “foo.o” that I would have expected to see if the double-suffix rule were compiling each and every “.c” file in the directory, as I expected it would have.

(stopping here; 5491 words)

I post my question on StackOverflow, and after awhile I get my answer. It turns out that a suffix rule like “.c.o:” doesn’t automatically compile a “.c” file just because it’s in the same directory. It only compiles the prerequisite into its corresponding target if said target is listed as a dependency of another rule. Since my “foo.o” file wasn’t listed as a dependency of another rule, it wasn’t compiled as part of the suffix rule’s execution.

OK so, to summarize what the two rules here are doing (we’re leaving out clean for now but will address it afterward):

.c.o:

This rule, when run by make, resolves to:

gcc -fno-common -c -o realpath.o realpath.c

I’m unable to find a man page for gcc on my local machine (I get “No manual entry for gcc” as an error when I run man gcc), so I have to Google around for what each of these things does. As far as I can tell, the components of this command are as follows:

gccis whatSHOBJ_CCresolves to. It’s initially set here as the variableCC, and is passed toshobj-confhere. It doesn’t get modified inshobj-conf(at least, not on my machine), and so it ends up as its original value when it’s run as a command bymake.- The

-fno-commonflag comes fromSHOBJ_CFLAGS. According togcc –help, it tells gcc to(c)ompile common globals like normal definitions. See below for a brief tangent.- TODO- explain what the implications of “compile common globals like normal definitions” means.

- TODO- explain what the

-fno-commonflag does. - The

-cflag tells gcc to “(o)nly run preprocess, compile, and assemble steps”, according togcc --help. - The

-oflag tells gcc to write its output to the file mentioned after the flag (in our case, “realpath.o”) - “realpath.c” is the input file that we’re asking gcc to compile.

../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib: realpath.o

This rule resolves to the following command on my machine:

gcc -dynamiclib -dynamic -undefined dynamic_lookup -o ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib realpath.o

Each of these components does something different:

gccdoes the same thing as in the firstmakerule- it invokes the Gnu C Compiler.-dynamiclib: according to the gcc docs, “When passed this option, GCC produces a dynamic library instead of an executable when linking, using the Darwin libtool command.” I’ll explain more in the tangent below on dynamic libraries.-dynamic: I’m not sure what this does, actually. I see a reference to it in the same gcc docs, but at the very bottom with no explanation on what it does. TODO- figure out how this is different from the-dynamiclibflag.-undefined: to be honest, at first this looked to me like a mistake, similar to the times when I’ve seen anullvalue be passed into a string-interpolation in JS and end up being resolved to the string “undefined”. That’s not the case here, since it’s explicitly set to this value here, inside the file “shobj-conf”. However, I’m not sure what its purpose is. TODO- figure out what the “undefined” flag does.dynamic_lookup: not sure what this does either. TODO- figure out what “dynamic_lookup” does.-o ../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib: this means that the output of thegcccommand should be the file “../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib”.realpath.o: this is the input file for thegcccommon here.

So while we can’t be sure what precisely this command is doing (since we don’t know what all the flags do), we can make a guess. Taken together, it appears that we are compiling “realpath.o” into a dynamic library named “../libexec/rbenv-realpath.dylib”.

UPDATE: after substantial searching, I Google the phrase “dynamic_lookup gcc”, and I find the following search result:

“…the option -undefined dynamic_lookup must be passed to the linker to indicate that unresolved symbols will be resolved at runtime.”

I read this to mean that the flag is “-undefined” with a flag parameter of “dynamic_lookup”, and that this combo tells gcc what to do when it finds an unresolved symbol. An example of an unresolved symbol is (I think?) is when a variable is mentioned in the code which hasn’t yet been defined. Since the whole purpose of what we’re doing here is to build a dynamic library (our faster, more performant “realpath” function), part of doing so is telling the code compiler what to do when it finds references to variables or functions that it doesn’t recognize.

I do think it’s a little weird that “-undefined dynamic_lookup” doesn’t seem to be documented in the gcc docs anywhere. Am I going crazy, or is it really and truly undocumented? I write a StackOverflow question about it. Eventually, someone responds that they do have a man entry for gcc, and that when they search for “undefined”, it says:

-undefined ... These options are passed to the Darwin linker. The Darwin linker man page describes them in detail.

I look up the “Darwin linker man page” online, and I find the following:

-undefined

Great, mystery solved. It looks like the docs confirm the info we found in the Github post.

Tangent: man pages

So why does the answerer have a man page for gcc on their machine, but I don’t have one on mine?

I Google "No manual entry for gcc", and find this StackOverflow post:

gcc isn't installed anymore by Xcode, it really installs clang and calls it gcc

usxxplayegm1:~ grady$ which gcc

/usr/bin/gcc

usxxplayegm1:~ grady$ /usr/bin/gcc --version

Configured with: --prefix=/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Developer/usr --with-gxx-include-dir=/usr/include/c++/4.2.1

Apple LLVM version 5.1 (clang-503.0.38) (based on LLVM 3.4svn)

Target: x86_64-apple-darwin13.0.2

Thread model: posix

you need man clang

I check my /usr/bin/gcc --version and get the following:

$ gcc --help

OVERVIEW: clang LLVM compiler

USAGE: clang [options] file...

...

So I suspect I’m having the same problem as the Stackoverflow person. And maybe the person who answered my StackOverflow question has gcc installed via a different source, maybe Homebrew or something.

I try to install gcc via Homebrew to find out, but when I do this (and try to verify it by which gcc), I continue to get /usr/bin/gcc, which I know is the system version of gcc, not the Homebrew version. Why?

I run ls -la /usr/local/bin/gcc* and get the following:

$ ls -la /usr/local/bin/gcc*

lrwxr-xr-x 1 myusername admin 31 Dec 3 10:35 /usr/local/bin/gcc-12 -> ../Cellar/gcc/12.2.0/bin/gcc-12

lrwxr-xr-x 1 myusername admin 34 Dec 3 10:35 /usr/local/bin/gcc-ar-12 -> ../Cellar/gcc/12.2.0/bin/gcc-ar-12

lrwxr-xr-x 1 myusername admin 34 Dec 3 10:35 /usr/local/bin/gcc-nm-12 -> ../Cellar/gcc/12.2.0/bin/gcc-nm-12

lrwxr-xr-x 1 myusername admin 38 Dec 3 10:35 /usr/local/bin/gcc-ranlib-12 -> ../Cellar/gcc/12.2.0/bin/gcc-ranlib-12

So Homebrew names this executable gcc-12, not gcc. Why is that? If the package name is gcc, I would expect there to be a gcc executable in /usr/bin/local as well. Is that an unreasonable expectation?

I type up another StackOverflow question and wait for an answer.

The next day, I realize that the name of the executable, and therefore the name of the command I have to type into my terminal, is probably due to decisions made by the authors of the Homebrew formula. I think it’d be a worthwhile exercise to put together a “Hello world” Homebrew package, to see how they’re made (and therefore the best practices around naming the executables), but that seems like a separate project that would distract me from my current mission. I capture it in my list of to-do’s, and I decide to table that for another day.

Tangent- Dynamic libraries

When I read the sentence “GCC produces a dynamic library instead of an executable…”, I was curious what the difference is between dynamic libraries and executables. I found this link, which says the following:

My key take-aways from this are:

- Static libraries are when we bundle all the necessary code into a single file, and are good when you want all the code you depend on in a single source file.

- Dynamic libraries are when you have files which are linked to other files. This allows those linked files to be depended on by multiple executables at once, without each executable needing to include it in the main source code.

- Since we aren’t including the dependency in our executable, that executable ends up being smaller in size.

- It also allows those linked files to be updated independently of the main executable file(s), without the executable needing to be recompiled.

- However, this comes at a cost- if the linked library is updated, that update could break the executable if the update is not backwards-compatible.

clean:

clean:

rm -f *.o ../libexec/*.dylib

This rule seems pretty straightforward, and we can find info on it in the Make manual:

Unsurprisingly, the clean rule tells make how to clean up after itself. Here we’re deleting any “.o” files we’ve created, along with the dynamic library file we created inside “../libexec”.

And I think that might be it for the RBENV project! That’s certainly all the folders (except for the Github workflows, which might be interesting to look at), and there are maybe one or two files in the root project directory that we could look at (i.e. the LICENSE file, where we could learn a little something about the different types of software licenses). But in terms of a first pass over the entire codebase, I think we’re close to dev-done!

At this point, I think it makes sense to go back through the things I’ve read and organize them into folders and files which match the directory structure of the project. This would make the info much easier to find, and therefore easier to review and edit.