If we haven’t mentioned this already, “rehashing” in the context of RBENV means “re-generating the shims”. This is a process which happens automatically, when you install a new gem, but you can also trigger it yourself. RBENV’s rehashing behavior is controlled mainly by two files- rbenv-rehash and rbenv-sh-rehash.

Since the libexec/rbenv-rehash and libexec/rbenv-sh-rehash files are closely related, we’ll look at both of them in this same post.

From the latest version of the README.md file, we see a description for this command:

rbenv rehashInstalls shims for all Ruby executables known to rbenv (

~/.rbenv/versions/*/bin/*). Typically you do not need to run this command, as it will run automatically after installing gems.

If we look at the path ~/.rbenv/versions/*/bin/*, we see two asterisks. The first one is after the versions/ directory. When I look inside ~/.rbenv/versions, I see a single sub-directory for each version of Ruby that I’ve installed via RBENV:

$ ls -la ~/.rbenv/versions/

total 0

drwxr-xr-x 4 myusername staff 128 Jun 5 09:41 .

drwxr-xr-x 17 myusername staff 544 Jun 11 10:04 ..

drwxr-xr-x 7 myusername staff 224 May 30 13:34 2.7.5

drwxr-xr-x 7 myusername staff 224 Jun 5 09:46 3.0.0

If I look inside one of these sub-directories, and further drill down into its bin/ sub-directory (as per the path mentioned in README.md), I see:

$ ls -la ~/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin/

total 792

drwxr-xr-x 88 myusername staff 2816 May 31 11:55 .

drwxr-xr-x 7 myusername staff 224 May 30 13:34 ..

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 538 May 30 13:37 bootsnap

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 538 May 30 13:37 brakeman

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 563 May 30 13:35 bundle

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 566 May 30 13:37 bundle-audit

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 556 May 30 13:39 bundle_report

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 565 May 30 13:35 bundler

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 568 May 30 13:37 bundler-audit

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 526 May 30 13:38 byebug

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 590 May 30 13:38 chromedriver

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 604 May 30 13:38 chromedriver-update

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 532 May 30 13:38 coderay

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 562 May 30 13:38 commonmarker

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 552 May 30 13:38 console

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 554 May 30 13:39 deprecations

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 526 May 30 13:38 dotenv

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 582 May 30 13:38 elastic_ruby_console

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 5097 May 30 13:35 erb

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 526 May 30 13:38 erubis

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 520 May 30 13:38 faker

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 532 May 30 13:38 fission

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 508 May 30 13:39 fog

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 532 May 30 13:39 foreman

-rwxr-xr-x 1 myusername staff 576 May 30 13:39 gecko_updater

...

Each bin/ sub-directory of each versions/* directory contains all the Ruby gems I’ve installed for that version of Ruby. So now we know that RBENV will maintain a different installation of a given gem for each version of Ruby you have installed.

Note, however, that it doesn’t install each of these copies automatically. For example, if I have Rails installed for Ruby v2.7.5 and I use rbenv local 3.0.0 to change my project’s Ruby version, I’ll have to re-install the rails gem (if I haven’t already done so) for this new Ruby version.

Now onto reading the files. As usual, first we’ll look at the usage comments.

Usage + summary comments

rbenv-sh-rehash doesn’t have any usage or summary comments, because we’re not meant to run that command directly. That command is executed elsewhere, as we’ll see below.

rbenv-rehash does contain comments, but only a one-liner Summary section:

# Summary: Rehash rbenv shims (run this after installing executables)

This doesn’t tell us anything that the README file didn’t already tell us.

That’s it for the usage comments, now on to the test file.

Tests

The create_executable function

After the bats shebang and the loading of test_helper, the first block of code is:

create_executable() {

local bin="${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/${1}/bin"

mkdir -p "$bin"

touch "${bin}/$2"

chmod +x "${bin}/$2"

}

Here we define a helper function named create_executable. This function gets called in tests further below. An example of a call to this function is:

create_executable "1.8" "ruby"

The first line of this function does the following:

- creates a local variable named

bin - sets the variable equal to a directory path composed of:

- the value of

RBENV_ROOT(ex.-~/.rbenv) - the string

/versions/ - the first argument

- the string

/bin

For example, if the value of this env var on my machine is /Users/myusername/.rbenv and the first argument I supply to the function is 1.8 (as it is above), then bin resolves to /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/1.8/bin.

We then:

- make a directory with this name.

- create an empty file in this directory with the same name as the 2nd argument to the function.

- modify this new file to make it executable, hence the function name

create_executable.

rbenv rehash without any parameters

First test in this file:

@test "empty rehash" {

assert [ ! -d "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims" ]

run rbenv-rehash

assert_success ""

assert [ -d "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims" ]

rmdir "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

}

This test does the following:

- As a sanity check test, we first assert that the

/shimsdirectory does not exist - We then run the

rbenv rehashcommand, and assert that it succeeded without any printed output lines. - We also assert that the

$RBENV_ROOT/shimsdoes now exist, implying that it’s the job ofrbenv rehashto create this dir. - Lastly, as a cleanup step, we remove the newly-created dir.

When we don’t have permission to create files in the /shims folder

Next test:

@test "non-writable shims directory" {

mkdir -p "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

chmod -w "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

run rbenv-rehash

assert_failure "rbenv: cannot rehash: ${RBENV_ROOT}/shims isn't writable"

}

- Here we again make the same directory, but then change its permissions via

chmod -w.- The

wsymbol means we’re changing the “write” permissions, and - the “-“ means we’re preventing the user from doing the thing that comes after “-“.

- So we’re preventing users (including the programs they execute, such as

rbenv rehash) from being able to write to this new directory.

- The

- After we run

rbenv rehash, we assert that:- the program failed and that

- a specific error message is output which tells the user that the directory is non-writable.

Protecting against two colliding attempts at hashing

Next test:

@test "rehash in progress" {

mkdir -p "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

touch "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/.rbenv-shim"

run rbenv-rehash

assert_failure "rbenv: cannot rehash: ${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/.rbenv-shim exists"

}

This test does the following:

- We start by making the same

/shimsdirectory that we made in the last 2 tests. - We then create an empty file called

.rbenv-shim, runrbenv rehash. - Lastly, we assert that:

- the program failed, and that:

- the error message tells the user that the

.rbenv-shimfile already exists.

Judging by the test description (“rehash in progress”), we can likely deduce that this file is created when the rehash process starts, and is deleted when the process is finished.

Creating the shim files

Next test:

@test "creates shims" {

create_executable "1.8" "ruby"

create_executable "1.8" "rake"

create_executable "2.0" "ruby"

create_executable "2.0" "rspec"

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/ruby" ]

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/rake" ]

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/rspec" ]

run rbenv-rehash

assert_success ""

run ls "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

assert_success

assert_output <<OUT

rake

rspec

ruby

OUT

}

Here we see the use of the create_executable helper function we analyzed at the start of this file. Our test does the following:

- We create 4 executable files:

- 2 in the “1.8/” version directory (one file named “ruby” and one named “rake”) and

- 2 in the “2.0/” version directory (one also named “ruby” and one named “rspec”).

- We then, as a sanity check, assert that there are no existing files within

$RBENV_ROOT/shimsnamed “ruby”, “rake”, or “rspec”. - We then run the “rehash” command, assert that it was successful.

- Lastly, we assert that:

- listing the contents of the

shims/sub-directory is successful, and that - its output includes “rake”, “rspec”, and “ruby”.

- listing the contents of the

Judging by the sanity check and final assertions in this spec, we can deduce that we created the “ruby” file twice (once in each directory) because we wanted to specifically assert that the final output would not include “ruby” twice.

Removing outdated shims

Next test:

@test "removes outdated shims" {

mkdir -p "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

touch "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/oldshim1"

chmod +x "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/oldshim1"

create_executable "2.0" "rake"

create_executable "2.0" "ruby"

run rbenv-rehash

assert_success ""

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/oldshim1" ]

}

This test does the following:

- As setup, we make our

shims/directory and add a file named “oldshim1” to it, which we make executable. - We then create two new executable files in a new directory named “versions/2.0/bin”:

- one executable named “rake” and

- the other named “ruby”.

- When we run

rbenv rehash, we assert that:- the command was successful, and

- the “oldshim1” file no longer exists.

This test shows us that, as part of creating the shims for the “newly-installed” rake and ruby executables, we also remove shims for any exist that no longer exist in our executables directory (presumably because they’ve been uninstalled).

Next spec:

@test "do exact matches when removing stale shims" {

create_executable "2.0" "unicorn_rails"

create_executable "2.0" "rspec-core"

rbenv-rehash

cp "$RBENV_ROOT"/shims/{rspec-core,rspec}

cp "$RBENV_ROOT"/shims/{rspec-core,rails}

cp "$RBENV_ROOT"/shims/{rspec-core,uni}

chmod +x "$RBENV_ROOT"/shims/{rspec,rails,uni}

run rbenv-rehash

assert_success ""

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/rails" ]

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/rake" ]

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/uni" ]

}

This is another test which covers the removal of outdated shims. It does the following:

- create a “versions/2.0/” directory with two executable files:

- one named “unicorn_rails” and

- one named “rspec-core”.

- Next we run the “rehash” command, to create the shims for these executables.

- We then copy the contents of the “rspec-core” file into three new shims:

- one named “rspec”,

- one named “rails”, and

- one named “uni”.

- We then update the permissions on all 3 cloned files to make them executable.

- We then re-run the “rehash” command and assert it was successful.

- Lastly, we assert that the 3 cloned files no longer exist.

In our test, there are 3 shims in the test (named rails, rake, and uni) which were not generated via rbenv rehash, and therefore they don’t belong to a corresponding executable. In real-world usage of RBENV, one case where this might happen is if an executable is un-installed. The shims for these executables are therefore considered “stale”.

In the case of our test, let’s look at the names of each of the 3 “stale” shims that we create. We can see that these names all partially (but not fully) overlap with the two executables that we created (unicorn_rails and rspec-core). This test ensures that a partial name match is not good enough, and that the name must match completely in order for the shim to be preserved.

When a Ruby binary name includes spaces

Next test:

@test "binary install locations containing spaces" {

create_executable "dirname1 p247" "ruby"

create_executable "dirname2 preview1" "rspec"

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/ruby" ]

assert [ ! -e "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/rspec" ]

run rbenv-rehash

assert_success ""

run ls "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

assert_success

assert_output <<OUT

rspec

ruby

OUT

}

This test does the following:

- As setup, we create two new sub-directories of the “versions” folder, both containing spaces.

- We also create one executable file in each new sub-directory.

- As a sanity check, we first assert that there are no shims in our

$RBENV_ROOTfolder associated with these new executables. - We then run the “rehash” command and assert it was successful.

- Lastly, we run “ls” on our “shims/” folder and assert that a new shim was created for each of the executable files we created in our setup.

This test ensures that even binaries whose parent folder contains spaces can be shim’ed.

Preserving the original value of IFS

Next test:

@test "carries original IFS within hooks" {

create_hook rehash hello.bash <<SH

hellos=(\$(printf "hello\\tugly world\\nagain"))

echo HELLO="\$(printf ":%s" "\${hellos[@]}")"

exit

SH

IFS=$' \t\n' run rbenv-rehash

assert_success

assert_output "HELLO=:hello:ugly:world:again"

}

This test covers this block of code, ensuring that any value of IFS passed to a hook is respected.

Remember, IFS stands for “internal field separator” and determines which character(s) the shell will use to perform word splitting.

The test does the following:

- We first create a hook for the “rehash” command named “hello.bash”, which contains the following executable logic:

hellos=(\$(printf "hello\\tugly world\\nagain"))

echo HELLO="\$(printf ":%s" "\${hellos[@]}")"

exit

- This hook creates a variable named “hellos” and sets it equal to “hello\tugly world\nagain”.

- This represents the words “hello”, “ugly”, “world”, and “again”, separated by (respectively) a tab character, a space character, and a newline character.

- The hook then

echos an assignment to a variable calledHELLO. - This assignment statement sets

HELLOequal to the above string, however it first splits that string based on whatever the current value of the IFS is, and then prefix each newly-split word with the “:” character before printing it.

- The test then runs the “rehash” command, ensuring that we set

IFSequal to the 3 characters we intend to split on (again, the tab char, the space char, and the newline char). - Lastly, we assert that:

- the command ran successfully, and that

- the word-splitting had the intended effect of replacing the old string

hello\tugly world\nagainwith the new string:hello:ugly:world:again.

The sh-rehash command

Next test:

@test "sh-rehash in bash" {

create_executable "2.0" "ruby"

RBENV_SHELL=bash run rbenv-sh-rehash

assert_success "hash -r 2>/dev/null || true"

assert [ -x "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/ruby" ]

}

This test creates a file under /versions/2.0 named ruby. It then runs rbenv sh-rehash, making sure to specify Bash as the shell program for RBENV to use. We then assert that the command ran successfully, and that the printed output contained the string:

"hash -r 2>/dev/null || true"

Lastly, we assert that a shim for ruby was created. The -x flag inside [ ... ] returns true if the file exists and is executable.

As we can see, the tests for rbenv-sh-rehash are in the same spec file as those of rbenv-rehash. That’s one reason why we’re tackling these two files together. We’ll find out further down how and when sh-rehash is invoked.

Last spec:

@test "sh-rehash in fish" {

create_executable "2.0" "ruby"

RBENV_SHELL=fish run rbenv-sh-rehash

assert_success ""

assert [ -x "${RBENV_ROOT}/shims/ruby" ]

}

This spec performs the same set of assertions as our previous test, but with the RBENV shell set to fish instead of Bash.

Code

As we’ve discovered from the fact that they share the same test file, the files rbenv-sh-rehash and rbenv-rehash are related to each other. We’ll analyze rbenv-sh-rehash first, and then move on to rbenv-rehash.

The first lines of code are familiar:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

[ -n "$RBENV_DEBUG" ] && set -x

# Provide rbenv completions

if [ "$1" = "--complete" ]; then

exec rbenv-rehash --complete

fi

- The Bash shebang.

- This time, there are no “Usage” or “Summary” instructions. This command is meant to be called by RBENV itself, not by users.

- Setting verbose mode if

RBENV_DEBUGis set. - Tab completion instructions.

Storing the name of the user’s shell

Next line of code:

shell="$(basename "${RBENV_SHELL:-$SHELL}")"

Here we set the variable shell equal to the filename (excluding the path) of either the value of RBENV_SHELL, or (if that doesn’t exist) the value of SHELL as a default. According to the man page, the basename command takes a string like /path/to/filename.txt and returns everything after the last / character. For example:

$ mkdir -p foo/bar/baz

$ touch foo/bar/baz/buzz

$ basename foo/bar/baz/buzz

buzz

Calling rbenv-rehash

Next lines:

# When rbenv shell integration is enabled, delegate to rbenv-rehash,

# then tell the shell to empty its command lookup cache.

rbenv-rehash

So rbenv-sh-rehash simply delegates to rbenv-rehash, but (according to the comments) it also clears out the shell’s command lookup cache.

Clearing the cache

That cache clearing happens below:

case "$shell" in

fish )

# no rehash support

;;

* )

echo "hash -r 2>/dev/null || true"

;;

esac

Here we inspect the value that we stored in shell earlier. If it’s fish, we execute a no-op. According to the comment, we can’t rehash if the user’s shell is fish.

If their shell is anything else, we echo a snippet of Bash code that the caller of rbenv-sh-rehash will execute via exec. This command includes the hash builtin.

I’m not familiar with the hash command, so I look up its help page:

bash-3.2$ help hash

hash: hash [-lr] [-p pathname] [-dt] [name ...]

For each NAME, the full pathname of the command is determined and

remembered...

OK so we’re remembering the full pathname of a command. Why would we want to do that?

I ask ChatGPT what the hash command is, and I get the following response:

Me:

What is the

hashcommand in Bash?ChatGPT:

The

hashcommand in Bash is a built-in command that is used to maintain a hash table of the locations of executable files. When you execute a command in Bash, the shell needs to search for the command’s location in the directories listed in thePATHenvironment variable. This search process can take some time, especially if there are many directories in thePATH.The

hashcommand helps improve the efficiency of command execution by caching the locations of executables in a hash table. When you run a command, the shell first checks the hash table to see if it has already located the executable. If the command is found in the hash table, the shell directly executes it without searching thePATH. This results in faster command execution.Here are some common uses of the

hashcommand:

hash: Without any arguments, thehashcommand displays the contents of the hash table, showing the commands and their locations that have been hashed.

hash -r: This option resets the hash table, removing all entries. It can be useful if you have updated or installed new executables and want the shell to search for them again.

hash <command>: If you provide the name of a command as an argument, thehashcommand locates the command’s location and adds it to the hash table. This can be handy if you want to manually update the hash table for a specific command.Overall, the

hashcommand in Bash helps improve the performance of command execution by caching the locations of executables, reducing the need for repeated searches in thePATHdirectories.

Got it, so hash is a performance optimization to prevent the shell from having to do a PATH lookup for the locations of command that it has previously executed.

The line which includes the call to hash was added as part of this issue/PR, which reported that RBENV users occasionally saw their ruby executable pointing to the system version of Ruby, as opposed to one managed by RBENV. Adding the hash -r block of code that we just analyzed, so that the hash table is emptied after every run of rbenv rehash, was the fix for this solution.

To double-check what ChatGPT told me, I decide to experiment with hash.

Experiment- the hash function

I start by printing out the current hash table, using the hash command with no arguments:

bash-3.2$ hash

hits command

1 /Users/myusername/.rbenv/libexec/rbenv

2 /usr/bin/man

So far it’s just the rbenv command and the command to open a man page.

Next, I try clearing the table with the -r flag:

bash-3.2$ hash -r

bash-3.2$ hash

hash: hash table empty

Great, that worked as expected.

Next, I try to manually add a command to the hash table:

bash-3.2$ hash -r

bash-3.2$ hash rbenv

bash-3.2$ hash

hits command

0 /Users/myusername/.rbenv/libexec/rbenv

Awesome. Now we can manually add commands to the table, if we need to.

Now I’m wondering if the table is automatically populated whenever I enter a command. I run rbenv local followed by hash again:

bash-3.2$ hash -r

bash-3.2$ rbenv local

rbenv: no local version configured for this directory

bash-3.2$ hash

hits command

1 /Users/myusername/.rbenv/libexec/rbenv

Great, so we don’t have to manually add values to the table; the shell will take care of that for us.

Looks like ChatGPT told us the truth.

One thing I notice is that my usage of the hash command itself is not reflected in the table. I ask ChatGPT about this as well:

Me:

What about builtin functions? Are they also reflected in the

hashtable?ChatGPT:

No, the hash table does not store built-in functions in Bash. The hash command only maintains a hash table for external executable commands.

Built-in functions in Bash are part of the shell itself and are not separate executable files. They are implemented directly within the shell’s code. As a result, they do not have separate locations in the file system that can be stored in the hash table.

When you use a built-in function in Bash, the shell recognizes it and executes it directly without relying on the hash table or searching for a separate executable file. Built-in functions are always available and do not require the shell to perform any file system operations to execute them.

So, while the hash command helps with caching and executing external commands efficiently, it does not have any effect on built-in functions in Bash.

I double-check this by Googling for a StackOverflow page, and find this one near the top of the results. It confirms the above:

Utilities provided as built-ins to the shell are not reported by hash.

It also tells us when the shell will clear the hash table on its own:

The table gets cleared on events that obviously invalidate the results (such as modifying

$PATH).

Furthermore, it tells us some interesting features of hash that the help page didn’t:

…it prints out how many times you hit which commands if you type it with no arguments.

To test this, I clear the table and run rbenv local again:

bash-3.2$ hash -r

bash-3.2$ hash

hash: hash table empty

bash-3.2$ rbenv local

rbenv: no local version configured for this directory

bash-3.2$ hash

hits command

1 /Users/myusername/.rbenv/libexec/rbenv

I see I’ve used rbenv once since clearing the table. I run the same rbenv command again and re-print the table:

bash-3.2$ rbenv local

rbenv: no local version configured for this directory

bash-3.2$ hash

hits command

2 /Users/myusername/.rbenv/libexec/rbenv

This time, the number next to the path to rbenv says 2 instead of 1. Pretty cool.

That’s the end of rbenv-sh-rehash.

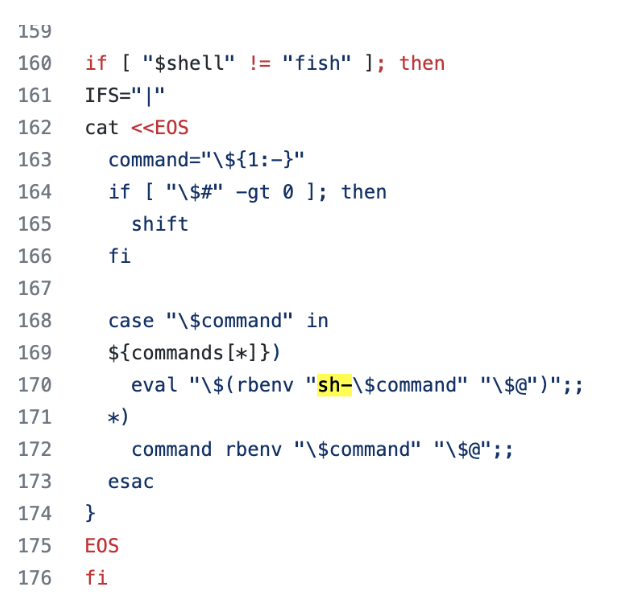

If we remember back to our read-through of rbenv-init, we saw that the rbenv shell function will run the sh- version of a user’s command, if that command is either rehash or shell:

So that’s where rbenv-sh-shell gets called. Let’s move on to “rbenv-rehash”.

rbenv-rehash

First lines of code:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Summary: Rehash rbenv shims (run this after installing executables)

set -e

[ -n "$RBENV_DEBUG" ] && set -x

- Bash shebang

- “Summary” remarks

set -etells Bash to exit immediately on first errorset -xtells Bash to print more verbose output, in this case only if theRBENV_DEBUGenvironment variable was set.

Making the shims/ directory

Next block of code:

SHIM_PATH="${RBENV_ROOT}/shims"

PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH="${SHIM_PATH}/.rbenv-shim"

# Create the shims directory if it doesn't already exist.

mkdir -p "$SHIM_PATH"

Here we create two new string variables, and use the first of them to make a new directory if it doesn’t already exist. This new directory will hold RBENV’s shims. The 2nd variable will be used later, and will contain the template code that we’ll use to build our shims.

Preventing multiple instances of rehash from running

Next block of code:

# Ensure only one instance of rbenv-rehash is running at a time by

# setting the shell's `noclobber` option and attempting to write to

# the prototype shim file. If the file already exists, print a warning

# to stderr and exit with a non-zero status.

set -o noclobber

{ echo > "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH"

} 2>| /dev/null ||

{ if [ -w "$SHIM_PATH" ]; then

echo "rbenv: cannot rehash: $PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH exists"

else

echo "rbenv: cannot rehash: $SHIM_PATH isn't writable"

fi

exit 1

} >&2

set +o noclobber

Luckily there’s a detailed comment which explains the purpose of the code below. That said, I still want to look up some of the syntax being used here.

The noclobber option

First off:

set -o noclobber

I look up the help entry for set, a command that we’ve encountered before. I see that -o is the flag you use when you want to set an option.

The above command turns on the bash noclobber option. According to this link:

The

noclobberoption prevents you from overwriting existing files with the>operator.If the redirection operator is

>, and the noclobber option to thesetbuiltin has been enabled, the redirection will fail if the file whose name results from the expansion of word exists and is a regular file.If the redirection operator is

>|, or the redirection operator is>and the noclobber option is not enabled, the redirection is attempted even if the file named by word exists.

Setting noclobber implies that we’ll be attempting to write to a new file, but we don’t want to do that if this file already exists. The name of that file is stored inside $PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH, which on my machine resolves to /Users/myusername/.rbenv/shims/.rbenv-shim. We attempt to create the file here:

{ echo > "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH"

} 2>| /dev/null ||

Output Grouping

We’ve seen the curly brace groups (i.e. { ....} ... { ... } before. This is called “output grouping”. According to Linux.com, “…you can also use { ... } to group the output from several commands into one big blob.”

An example here:

The command:

echo "I found all these PNGs:"; find . -iname "*.png"; echo "Within this bunch of files:"; ls > PNGs.txtwill execute all the commands but will only copy into the PNGs.txt file the output from the last ls command in the list. However, doing

{ echo "I found all these PNGs:"; find . -iname "*.png"; echo "Within this bunch of files:"; ls; } > PNGs.txtcreates the file PNGs.txt with everything, starting with the line “I found all these PNGs:”, then the list of PNG files returned by find, then the line “Within this bunch of files:” and finishing up with the complete list of files and directories within the current directory.

So we’re just grouping the output of the commands inside the curly braces, and redirecting their combined output to the destination to /dev/null. We don’t care about that output- we only care whether the creation of $PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH returned a 0 exit code.

If our attempt to create the file produces any error output, we redirect it to /dev/null using 2>|. Normally, we’d use 2> without the |, but because we have noclobber turned on, 2> won’t work.

Note that sending output to /dev/null, with noclobber turned on, will actually work for some people:

$ set -o noclobber

$ echo "foo" > /dev/null

$

I researched why this line of code was added to RBENV, and the PR which added it says that some versions of Bash don’t permit this behavior. Your mileage may vary depending on which version of Bash you have on your machine.

FWIW, I posted a StackExchange question asking why this might be happening, and eventually the answer comes back that /dev/null is treated differently by noclobber, since it’s considered a “non-standard file”.

echo > vs. touch to create a file

I noticed the use of echo > <filename> here, rather than touch <filename>, which I thought was the canonical command that is used to create a new, empty file. I Google “difference between echo and touch in bash”, and I find this StackExchange link. The difference is that:

touchwill create the file if it doesn’t already exist, or update the file’s “created_at” and “updated_at” timestamps if it does exist.- Both

echo >andecho >>will create a file if it doesn’t exist.echo >will overwrite the file if it does exist, whileecho >>will append to the file if it exists.

Based on the above, I think what’s happening here is that we’re using the file as a “lock file”, i.e. an indicator that the rehash action is in-progress. The combination of set -e, set -o noclobber, and echo > <filename> means that the script will attempt to create a new file, but if the file already exists, the script will throw an error and then exit. That achieves the behavior of preventing more than one rehash from being performed at once, since presumably we’ll delete the file when we’re done.

Printing an error message if a rehash is already in progress

Moving on to the next block of code (i.e. what happens after the || characters):

{ if [ -w "$SHIM_PATH" ]; then

echo "rbenv: cannot rehash: $PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH exists"

else

echo "rbenv: cannot rehash: $SHIM_PATH isn't writable"

fi

exit 1

} >&2

If the previous attempt at creating the new file fails, we reach this block of code. Here we check whether the SHIM_PATH directory is writable.

- If it is, we assume that the failure resulted because the file already exists.

- If it’s not writable, we echo a different error message to that effect.

Either way, we exit with a non-zero return status. Whichever error message we echo, we redirect that message to STDERR via >&2.

Turning off noclobber

Next line of code:

set +o noclobber

Here we just turn off the noclobber option that we turned on before we attempted to create the PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH file.

That’s it for the lock file logic!

Telling Bash to clean things up when we’re done

Next block of code:

# If we were able to obtain a lock, register a trap to clean up the

# prototype shim when the process exits.

trap remove_prototype_shim EXIT

remove_prototype_shim() {

rm -f "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH"

}

Here we invoke the trap command. The docs tell us that trap lets the user execute arbitrary code when the shell receives one or more specified signals.

In this case, we’re telling the shell to call the remove_prototype_shim function whenever it receives an EXIT signal (i.e. whenever the process exits, whether normally or abnormally). That function is defined on the next few lines of code, and it force-deletes the temporary .rbenv-shim file that’s created.

This is how the lock file eventually gets deleted, so that subsequent calls to rbenv rehash can once again be made.

Experiment- using trap

I write the following script:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

cleanup() {

echo "Cleanup function called."

# Add cleanup commands here

}

trap cleanup EXIT

# Some other commands or script code

echo "This is the main part of the script."

echo "Performing some tasks..."

# Simulating an error condition

non_existing_command

echo "This line will not be executed due to the error above."

This script does the following:

- Calls

set -eto exit on the first error. - Defines a function called

cleanup(), which just prints a string (but which could do any arbitrary task we specify) - Calls the

trapbuiltin, telling the shell to call ourcleanupfunction when it receives theEXITsignal - Prints some arbitrary text to the screen, to prove that our script is running normally

- Call a known-invalid command to trigger an error (and therefore, because we called

set -e, an exit) - Call

echowith a string which we know will not print to the screen.

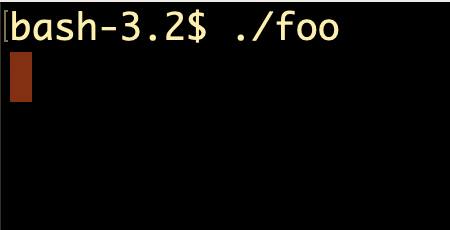

When we run the script, we see:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

This is the main part of the script.

Performing some tasks...

./foo: line 17: non_existing_command: command not found

Cleanup function called.

Because we called trap cleanup EXIT, and because our initial call to set -e caused the shell to exit (i.e. send an EXIT signal) when it encountered an error, we saw our "Cleanup function called" script print to the screen.

Shell signals

We can use the trap command with other shell signals too. A full list of signals can be printed via the trap -l command:

bash-3.2$ trap -l

1) SIGHUP 2) SIGINT 3) SIGQUIT 4) SIGILL

5) SIGTRAP 6) SIGABRT 7) SIGEMT 8) SIGFPE

9) SIGKILL 10) SIGBUS 11) SIGSEGV 12) SIGSYS

13) SIGPIPE 14) SIGALRM 15) SIGTERM 16) SIGURG

17) SIGSTOP 18) SIGTSTP 19) SIGCONT 20) SIGCHLD

21) SIGTTIN 22) SIGTTOU 23) SIGIO 24) SIGXCPU

25) SIGXFSZ 26) SIGVTALRM 27) SIGPROF 28) SIGWINCH

29) SIGINFO 30) SIGUSR1 31) SIGUSR2

Note that the above works in Bash, but not zsh.

You’ll notice that the “signal” we used in our first trap example, i.e. EXIT, is not listed in the above signals. That’s because EXIT is actually a special “catch-all” that can be used to catch any signal.

Let’s try modifying our original trap experiment to catch SIGINT, a relatively common signal that is triggered when you hit Ctrl+C on your keyboard.

I update the script to look like so:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

cleanup() {

echo "Cleanup function called."

exit

# Add cleanup commands here

}

trap cleanup SIGINT

# Some other commands or script code

echo "This is the main part of the script."

echo "Performing some tasks..."

# Simulating an error condition

while [ "a" = "a" ]

do

foo="foo"

done

echo "This line will not be executed due to the error above."

I changed the trap call from EXIT to SIGINT, and replaced the call to non_existing_command with a while loop that will never terminate by itself. When I run this script, my terminal hangs:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

This is the main part of the script.

Performing some tasks...

When I hit Ctrl-C, I see the following:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

This is the main part of the script.

Performing some tasks...

^CCleanup function called.

bash-3.2$

The output ^CCleanup function called. represents the output of Ctrl-C (i.e. the ^C part of the output) plus the same output of the cleanup() function as before.

Finding the path to the RBENV command

Next block of code:

# Locates rbenv as found in the user's PATH. Otherwise, returns an

# absolute path to the rbenv executable itself.

rbenv_path() {

local found

found="$(PATH="$RBENV_ORIG_PATH" command -v rbenv)"

if [[ $found == /* ]]; then

echo "$found"

elif [[ -n "$found" ]]; then

echo "$PWD/${found#./}"

else

# Assume rbenv isn't in PATH.

local here="${BASH_SOURCE%/*}"

echo "${here%/*}/bin/rbenv"

fi

}

The comments at the top of the function tell us exactly what it does:

Locates rbenv as found in the user’s PATH. Otherwise, returns an absolute path to the rbenv executable itself.

The implementation is as follows.

Searching for the path to rbenv

local found

found="$(PATH="$RBENV_ORIG_PATH" command -v rbenv)"

We start by creating a local variable named found. We tell the shell to search $RBENV_ORIG_PATH (not $PATH) for the filepath of the command rbenv. RBENV_ORIG_PATH is set here, and represents the original value of PATH before RBENV modifies it to add the libexec/ directory, as well as things like plugins.

We set the found variable equal to the first filepath to the rbenv executable that we find in our original, un-modified PATH. On my machine, this resolves to /usr/local/bin/rbenv.

Handling an absolute path

if [[ $found == /* ]]; then

echo "$found"

If this found value starts with / (i.e. if the found path is an absolute path starting from the machine’s root directory), then the return value of the rbenv_path function is the value of found.

Handling non-absolute paths

elif [[ -n "$found" ]]; then

echo "$PWD/${found#./}"

If the path doesn’t start with / but does exist, we make an assumption that the executable was found in the current directory. Therefore, we shave any “./” off the beginning of found, and prepend it with the full path to the current directory (via the $PWD variable). We then print that value to stdout.

Handling the case where no path was found

else

# Assume rbenv isn't in PATH.

local here="${BASH_SOURCE%/*}"

echo "${here%/*}/bin/rbenv"

fi

Lastly, if that 2nd condition also fails, we fall back to looking in RBENV’s BASH_SOURCE directory, which always contains the filepath for the file that’s currently being run. On my machine, the returned value in this case would be /usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/1.2.0/bin/rbenv. Here are the docs for the BASH_SOURCE variable, as well as many other env vars.

Why $RBENV_ORIG_PATH and not $PATH?

I was confused about why this $RBENV_ORIG_PATH variable was needed, when it seemed like $PATH would be the less-surprising choice. I pulled up the PR which introduced this line of code to find the answer.

The rbenv_path function was added to fix a bug which only presented itself when it was installed with a popular, widely-used package manager called Homebrew (as opposed to, for example, installing RBENV directly from the source code). The bug worked as follows:

- When RBENV adds a shim, that shim has to execute the

rbenvcommand. To ensure this could happen even if that command wasn’t found inPATH, the shim uses the absolute path to therbenvexecutable file. - When installed via Homebrew, the absolute path to that executable looks like this:

/usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/<VERSION>/libexec/rbenv

- In this path,

<VERSION>represents the version number of RBENV that the user is currently using. - However, according to the Homebrew docs, “Homebrew automatically uninstalls old versions of each formula that is upgraded with brew upgrade, and periodically performs additional cleanup every 30 days.”

- If I generate a shim for

rubyusingv1.0of RBENV, and then I upgrade my RBENV tov2.0, the previously-generated shim (which is still in my$PATHand will still be executed when I typerubyin my terminal) will break, because it’s pointing to an absolute filepath which includes the oldv1.0version of RBENV.

To further explore the bug, I changed the code in rbenv-rehash from this PR back to its original version, and re-ran rbenv rehash to see what shim would be generated. Previously, rbenv rehash would cause the shim to run:

exec "/usr/local/Cellar/rbenv/<HOMEBREW VERSION>/libexec/rbenv" exec "$program" "$@"

After this PR’s change, the new line of code (at least, in my case) becomes:

exec "/usr/local/bin/rbenv" exec "$program" "$@"

So that’s how this bug was fixed. Instead of immediately using the absolute path to libexec/rbenv (which contains the version number), RBENV first tries to use any paths specified by a package manager such as Homebrew, including symlinks generated by Homebrew to the correct rbenv executable. It then falls back to the original approach if no such Homebrew-friendly paths were found.

Generating the shim

The next block of code looks really long, but most of it is code that we’ve already reviewed:

# The prototype shim file is a script that re-execs itself, passing

# its filename and any arguments to `rbenv exec`. This file is

# hard-linked for every executable and then removed. The linking

# technique is fast, uses less disk space than unique files, and also

# serves as a locking mechanism.

create_prototype_shim() {

cat > "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH" <<SH

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -e

[ -n "\$RBENV_DEBUG" ] && set -x

program="\${0##*/}"

if [ "\$program" = "ruby" ]; then

for arg; do

case "\$arg" in

-e* | -- ) break ;;

*/* )

if [ -f "\$arg" ]; then

export RBENV_DIR="\${arg%/*}"

break

fi

;;

esac

done

fi

export RBENV_ROOT="$RBENV_ROOT"

exec "$(rbenv_path)" exec "\$program" "\$@"

SH

chmod +x "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH"

}

This function creates uses the cat command to print a multi-line string to the temporary .rbenv-shim file, and makes that file executable. That’s all it does. Everything from the <<SH on the first line of the body to the SH on the 2nd-to-last line of the body is a heredoc containing the shim code that we looked at here, so there’s no need to go over the code again.

Removing outdated shims

Next block of code:

# If the contents of the prototype shim file differ from the contents

# of the first shim in the shims directory, assume rbenv has been

# upgraded and the existing shims need to be removed.

remove_outdated_shims() {

local shim

for shim in "$SHIM_PATH"/*; do

if ! diff "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH" "$shim" >/dev/null 2>&1; then

rm -f "$SHIM_PATH"/*

fi

break

done

}

The comments here give us a great idea of what’s going on. In this function definition, we compare the prototype shim file with each file in the SHIM_PATH directory. But there’s a caveat- we don’t actually end up checking each file.

It looks like we do, because we’re using a for loop, but the comments say we only check “the first shim in the shims directory”. That’s because the contents of all the shims are the same, so we can assume that if the first file is the same as the shim file, then the rest are as well.

The tool we use to compare the files is the diff command. Let’s see how it works with an experiment.

Experiment- the diff command

I create a file named foo, containing the following text:

Hello world

Foo

Baz

I create a 2nd file named `bar, containing some text that’s the same and some which is different:

Hello globe

Foo

Bar

Buzz

When I run the diff command against these two files, I see:

$ diff foo bar

1c1

< Hello world

---

> Hello globe

3c3,4

< Baz

---

> Bar

> Buzz

- The first line of output,

1c1, means that there’s a difference between line 1 offooand line 1 ofbar. - The next 3 lines show the difference between the first line of the two files, with a divider

---in between the respective files. - The next line,

3c3,4shows that there’s a difference between line 3 offooand lines 3 through 4 ofbar. - The last block again shows what that difference is.

Lastly, I check the return code of that diff command, making sure it’s the very next command I run after diff:

$ diff foo bar

1c1

< Hello world

---

> Hello globe

3c3,4

< Baz

---

> Bar

> Buzz

$ echo "$?"

1

So if there is a diff, the exit code will return 1.

I then create two new files, named baz and buzz, each containing a single character ("a"):

$ echo "a" > baz

$ echo "a" > buzz

When I diff them and check the exit code again, I see no diff and a 0 exit code:

$ diff baz buzz

$ echo "$?"

0

So if there is a difference between two files, diff prints that difference and returns a non-zero exit code. If there’s no difference, it prints an empty string and returns a zero exit code.

Back to our code. We check the following condition:

if ! diff "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH" "$shim" >/dev/null 2>&1; then

We run diff "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH" "$shim" to check the diff between two files. If there is no diff, then:

- the command’s exit code will be 0,

- the

ifcheck will be false (because of the!before thediffcommand), and - we will execute the code inside the

ifblock.

If there is a diff, the command’s exit status is 1, we negate that non-zero status with the ! symbol, and we skip the if block.

Note that we send any output from diff to /dev/null, because we don’t actually care what the diff is, only whether such a diff exists. We do care if an error happens, however, so we send any STDERR output to STDOUT via 2>&1.

If we reach the code inside the if check, we know we’ve found a shim file which doesn’t match our prototype. In that event, it’s safe to assume that our prototype shim file contains newer code than our current shims, so we delete the current shims via the rm -f "$SHIM_PATH"/* command.

The last line of code in this for loop is a break statement. This break is what ensures we only check the first shim in the SHIM_PATH. It’s a performance optimization which ensures that we only execute one iteration of the for loop. Since all the shims should always be the same, checking each one is superfluous.

Next block of code:

# List basenames of executables for every Ruby version

list_executable_names() {

local version file

rbenv-versions --bare --skip-aliases | \

while read -r version; do

for file in "${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/${version}/bin/"*; do

echo "${file##*/}"

done

done

}

This block implements a function called list_executable_names.

The function starts off by creating two local variables, called version and file. It calls rbenv-versions –bare –skip-aliases and pipes the results to the next command.

- The

--bareflag strips out thesystemversion and any extra information, such as the source file of the Ruby version setting. - The

--skip-aliasesflag ensures that the folders that we use to derive our Ruby versions don’t contain any aliases.

What we’re left with is a list of Ruby versions installed by RBENV, as we can see if we test out this command in our terminal:

$ rbenv versions --bare --skip-aliases

2.7.5

3.0.0

As mentioned before, we then pipe the list of versions to a while loop, effectively iterating over each version. For each item in that output, we use the read command to create a local variable called version containing that version number.

We then use the version variable to create a path to that version’s directory of shims:

"${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/${version}/bin/"*

For example, if version is 2.7.5, then the directory looks like "${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/2.7.5/bin/"*. The asterisk at the end indicates that we’re using a pattern known as either “filename expansion” or “globbing”. When used with a for loop like we’re doing here, it means that we’re iterating over each file in the ${RBENV_ROOT}/versions/2.7.5/bin/ directory.

Lastly, for each file in the directory, we use the parameter expansion pattern "${file##*/}" to take just the filename, removing any directory path that precedes it. So /Users/myusername/.rbenv/versions/2.7.5/bin/rails becomes just rails.

So to summarize the list_executable_names function- for every version of Ruby we have installed with RBENV, we echo the name of every single one of the gems installed for that Ruby version.

The read builtin

In the above function, we used the read builtin to read a version number from stdin and assign the value to a variable named version. Since read is a builtin, it won’t have a man entry, so let’s look at the first few lines of its help entry instead:

read: read [-ers] [-u fd] [-t timeout] [-p prompt] [-a array] [-n nchars] [-d delim] [name ...]

One line is read from the standard input, or from file descriptor FD if the

-u option is supplied, and the first word is assigned to the first NAME,

the second word to the second NAME, and so on, with leftover words assigned

to the last NAME. Only the characters found in $IFS are recognized as word

delimiters. If no NAMEs are supplied, the line read is stored in the REPLY

variable.

A simplfied way of using this command is shown in the experiment below.

Experiment- the read command

I make the following Bash script, called foo:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

read foo bar baz

echo "$foo"

echo "$bar"

echo "$baz"

echo "Finished!"

When I run ./foo in my terminal, I see:

The terminal is waiting for me to type in some input. I type some words in and hit “Enter”:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

Jan Feb March

Jan

Feb

March

Finished!

Next I try to enter more than just 3 words as input:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

Jan Feb March April May June

Jan

Feb

March April May June

Finished!

So when there are more than the expected number of variables passed, read will use the last variable to capture any input that remains.

What about when there’s no variable names specified? How will we know what to capture? The help script stated that:

If no NAMEs are supplied, the line read is stored in the REPLY variable.

To test this, I update my script to look like this:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

read

echo "$REPLY"

echo "Finished!"

When I run the script and type some input, I see:

bash-3.2$ ./foo

Foo bar bazz buzzzz

Foo bar bazz buzzzz

Finished!

So read takes input from STDIN and stores it in one or more variables, after which you can use those variables for whatever purpose you want.

Lastly, because read takes its input from STDIN, we can take advantage of that to iterate over each item in a series of input. Our list_executable_names function above did exactly that, and we can recreate its effects to see how this works.

I have a file called foo containing the following text:

foo

bar

baz

I do the following:

$ cat foo | while read -r buzz; do

pipe while> echo "hello $buzz"

pipe while> done

hello foo

hello bar

hello baz

We added the string hello to each line of our input file. This is a trivially simply example, but it shows how read and while loops can be used together to iterate over input.

Next block of code:

# The basename of each argument passed to `make_shims` will be

# registered for installation as a shim. In this way, plugins may call

# `make_shims` with a glob to register many shims at once.

make_shims() {

local file shim

for file; do

shim="${file##*/}"

registered_shims+=("$shim")

done

}

This function makes two local variables, one named file and one named shim. It then iterates over each of the arguments provided to the function (remember, for file; do is short for for file in "$@"; do).

For each argument, we shave off everything except the filename itself, to get the name of the shim. We then add that shim name to an array of other shim names.

One thing you might notice is that, even though this function is called make_shims, it doesn’t actually make anything. It just adds a shim’s name to a running list of shims to make. Normally I’d say that misnamed functions are a problem, but this function and the next one (register_shim) are actually no longer used in this file.

I asked about this in a PR, and the response was that, since the rbenv rehash command supports plugins, these two functions are kept in-place for backwards compatibility with any plugins that might still use them.

Experiment- Arrays in Bash

The registered_shims+=("$shim") might look strange. registered_shims is an array of strings, and here we’re adding a new item to that array. This is something we’ve never needed to do until now.

Here’s a stripped-down example in my terminal:

bash-3.2$ foo=(1 2 3 4 5)

To create an array, you wrap the items with parentheses and separate them with spaces.

To concatenate something to the end of that array, you do a simple += operation and pass the new value, which is also wrapped in parens:

bash-3.2$ foo+=(6)

If we try to print out the array without any special syntax, we’ll only see the first of its items in our output:

bash-3.2$ echo $foo

1

To print out each item, we have to use parameter expansion, plus some syntax that looks like [@]. I can’t find an official source to tell me what the name of this syntax is, so I’ll call it “array expansion”:

bash-3.2$ echo "${foo[@]}"

1 2 3 4 5 6

Registering a shim

Next block of code:

# Registers the name of a shim to be generated.

register_shim() {

registered_shims+=("$1")

}

This function does the exact same thing we just discussed in the previous block of code- it just adds a single shim name to the running list of shims that is held in the registered_shims variable. Again, like the previous function, this one is also an orphan function that isn’t called anywhere.

Actually installing the shims

Next block of code:

# Install all the shims registered via `make_shims` or `register_shim` directly.

install_registered_shims() {

local shim file

for shim in "${registered_shims[@]}"; do

file="${SHIM_PATH}/${shim}"

[ -e "$file" ] || cp "$PROTOTYPE_SHIM_PATH" "$file"

done

}

This new function has a similar setup to the make_shims function above, but there is a difference:

- It creates two local variables, just like

make_shimsdoes. - But then instead of iterating over the arguments to the function, it iterates over the array of previously-registered shims.

- Here, “registered” means any shim whose name has been added to the

registered_shimsarray. - That can happen via either the

register_shimor themake_shimsfunctions, or (further down) line 155, which sets the list of shims based on the return value of thelist_executable_namesfunction.

For each of these registered shims, we create a filename string for that shim in the correct directory (SHIM_PATH), and then we check if that file exists. If it doesn’t, we create it by duplicating the prototype file and giving the duplicate the name of our new filepath.

Removing stale shims

Next block of code:

# Once the registered shims have been installed, we make a second pass

# over the contents of the shims directory. Any file that is present

# in the directory but has not been registered as a shim should be

# removed.

remove_stale_shims() {

local shim

local known_shims=" ${registered_shims[*]} "

for shim in "$SHIM_PATH"/*; do

if [[ "$known_shims" != *" ${shim##*/} "* ]]; then

rm -f "$shim"

fi

done

}

The goal of this function is to remove files which point to un-registered shims from SHIM_PATH. As the comment indicates, this is a clean-up step after the installation process has finished.

- We create two local variables, one named

shimand one namedknown_shims. - We set

known_shimsequal to the contents ofregistered_shims. - Then for each shim in

SHIM_PATH, we check whether that shim’s name is included in the list of known shims. - If it’s not, we delete it from the filesystem.

Setting the nullglob option

Next line of code:

shopt -s nullglob

As we’ve seen before, this line sets the nullglob option. With this option set, a pattern which doesn’t match any files will expand to an empty string, rather than itself.

This is useful when attempting to iterate over all files in a directory, such as here in remove_outdated_shims, or here in remove_stale_shims.

Creating the prototype shim file and removing outdated shims

Next block of code:

# Create the prototype shim, then register shims for all known

# executables.

create_prototype_shim

remove_outdated_shims

Here’s where we call the function that creates and populates the contents of the .rbenv-shim file, the prototype which is then used to create all the actual shims.

We also call the function which checks whether the shims are out-of-date (via the diff command), and removes them if they are.

Registering the shims

Next block of code:

# shellcheck disable=SC2207

registered_shims=( $(list_executable_names | sort -u) )

Let’s come back to the shellcheck line a bit later. For now, we’ll focus on the 2nd of the two lines.

The outer code (registered_shims=( ... )) creates an array variable named registered_shims. As we saw above foo=() creates an empty array, and foo=( ... ) creates a non-empty array, populated with whatever the ... is, inside the parentheses.

The code inside those outer parentheses, $(list_executable_names | sort -u), is command substitution. This code populates the registered_shims list with the return value of the list_executable_names function we defined above. That return value is the executable contents of each of RBENV’s version directories.

The call to sort -u was added as part of this PR, whose goal was to speed up the execution of the shim generation process. sort -u eliminates identical executable names from the list of shims to generate, before generating those shims.

So if a person has 10 Ruby versions installed via RBENV, and each version has its own copy of the rails gem installed, the code only registers the rails gem once. Which means only one rails shim will get created.

Returning to the shellcheck line. This line disables the shellcheck rule defined here. This rule prevents the shell “…from doing unwanted splitting and glob expansion, and therefore avoid(s) problems with output containing spaces or special characters.”

Here’s the intention behind the rule. Let’s say we have a command, mycommand, which generates some output with spaces and special characters:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

foobar() {

echo "Hello world !"

}

If we use command substitution to capture the output of this function in an array, it would look like this:

array=( $(foobar) )

The problem is that, because we didn’t wrap $(foobar) with quotes, the shell splits the words using whitespace as a delimiter. So our array now has 3 items in it:

Hello

world

!

We lost the (intentional) spacing between ‘Hello’, ‘world’, and ‘!’. Apparently, if we follow shellcheck’s guidelines and use either the mapfile or read -a commands, we would avoid this problem.

The reason we’re able to disregard the shellcheck rule here is because we don’t expect this scenario to happen. We know what the output of list_executable_names | sort -u will be, and we know it won’t include any intentional, excess spaces.

Executing hook logic

Next block of code:

# Allow plugins to register shims.

OLDIFS="$IFS"

IFS=$'\n' scripts=(`rbenv-hooks rehash`)

IFS="$OLDIFS"

for script in "${scripts[@]}"; do

source "$script"

done

We’ve seen this pattern before. We pull any hook files for the rehash command using rbenv-hooks rehash, taking care to split the output of that command correctly based on the anticipated \n delimiter, and then re-set IFS back to its original value afterward. We then iterate over this array of hook filepaths, and source each one.

Installing the new shims and removing the stale ones

Last block of code for this file:

install_registered_shims

remove_stale_shims

Here we call the function which creates a new shim file for each registered shim (if one doesn’t already exist). We also call the function which removes any file in SHIM_PATH if it doesn’t correspond to one of our registered shims.

And that’s the end of the file!

Why not use symlinks instead of real files?

You may have noticed that the files we generate are regular files, generated via the cp command. They are explicitly not symlinks, generated via the ln -s command.

Why not use symlinks? In other words, we could generate a symlink to point to a single canonical regular shim file, rather than do a full copy of the prototype file into a new shim file. We learned when we read the rbenv command’s code that regular files take up much more space than symlinks. And because of its smaller file size, generating a symlink would likely be faster than generating a regular file, making our rehash command more performant.

This was actually the first approach that RBENV took. I searched for “symlink” in RBENV’s Github repo, and I found this PR which shows that the (much shorter) rbenv-rehash file used to contain this:

for file in ../versions/*/bin/*; do

ln -fs ../bin/rbenv-shim "${file##*/}"

done

Very quickly, however, an issue came up, something to do with a dependency on hard-coded relative pathnames (the issue is light on details). And the decision was made to replace symlinks with regular files.

Interestingly, only 2 days later in the repo’s history, the core team made a decision to switch from regular files to hardlinks, a sort of middle ground between symlinks and regular files.

Unfortunately, that decision created problems of its own. Hardlinks are not supported by some filesystems, as this PR points out. So the maintainers bit the bullet and switched back to regular files again. The cost of this was (very slightly) less-performant code, but the benefit was portability across a wider variety of file systems.

That’s it for this file. On to the next one.